It is always stimulating to come across an early modern text that feels (as we say) transgressive. In the mid-seventeenth century, press censorship temporarily lapsed, and the printing presses were numerous and nimble enough to let all sorts of voices speak. Broadside ballads had always allowed a broad range of robust sentiment, these two texts both have a transgressive spirit, stronger and truer than in most of the elite writing from which we so carefully refine it these days.

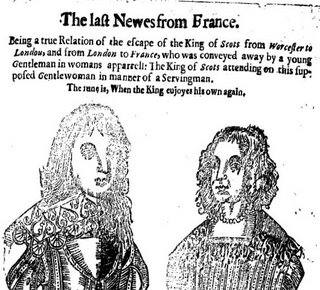

The Last News From France purports to tell a story of how the future Charles II escaped after the Battle of Worcester. The gender switchings are harder to keep in mind than those in As You Like It: in the main, Charles dresses as a servingman, whose Lady, ‘Mistress Ann’, is actually a young gentleman in disguise. You only learn this fact from the ballad’s heading: in the ballad itself, the speaker has effectively become female. At one point in the ballad a maximum of reversal is enjoyed: ‘He of me a service did crave / and often-times to me stood beare / In womans apparel he was most brave / and on his chin he had no hare’. First, the ‘King of Scots’ stands bare-headed to his Master-Mistress, the next moment, he is dressed as a woman. That ‘Womans’ adds such confusion that one half wonders if it was a misprint (but, say, a ‘servingman’ could not dress up ‘most brave’ without Charles starting to look like himself again, even if without a Cavalier’s Van Dyke beard). During the historical Charles's escape, the main problem was his distinctive height: forces were searching for 'a tall black man, over two yards high'. But the ballad writer isn't troubled by plausibilities of disguise, and pops him into 'womans apparel'.

Anyway, in the ballad, the two pass (most implausibly) through

But even so, in this defiantly, even cockily Royalist ballad (it was written to be sung to the tune ‘When the King enjoys his own again’, Matthew Parker’s definitive ballad for the Stuart cause), there is this heady, even sexy pleasure in the King becoming a servingman. During the romance of escape, he even becomes a woman. See, though, a kind of delicacy: to enjoy this kind of royal servitude to him, the speaker has had to become ‘Mistress Ann’. As the son of his courtly father, Charles can (it seems) with more seemliness ‘serve’ a woman. ‘Where ever I came / My speeches did frame / So well my Waiting man to free’: if, as a necessity to set the King ‘free’, the King has to be made subject, and ordered around, well, a woman can just about permissibly do this.

The Wanton Wife of BATH is an absolute ripper: ‘In

I suppose that only in bits of medieval drama do you hear this voice of outrageous commonsense response to the Bible and its gallery of doubtful customers. It has been biting pretty close to the bone: Chaucer’s Wife of Bath is fighting her corner all too well, establishing herself as the moral equal or superior to a mixture of patriarchs, biblical kings, and disciples. The raunchiest voice in the Canterbury Tales seems ready to instate the text from which she comes - when it comes to teaching morality - ahead of the Bible.

Of course, all this subversion ends with containment, in its perfect form: Christ himself comes to hear what the fuss is about. Of him, she craves mercy, she repents, agrees humbly to all his charges about her lewd life and not living to his teachings, but still has the courage to cite the precedents: the thief on the cross, the prodigal son forgiven, the strayed sheep. And Christ forgives her soul, and lets her enter into joy.

I can only imagine a clergyman biting his lip at this gleeful invention, in which the unruliest woman in an English book denounces the Bible as a rogues’ gallery, and makes an unanswerable case for mercy based on precedents, not morality. Maybe quite a few copies of both these ballads were torn up by vexed readers, but it is pleasant to imagine a folded up copy being taken out of an apron pocket, and somebody starting to sing either ballad to listeners that she knew would approve.

No comments:

Post a Comment