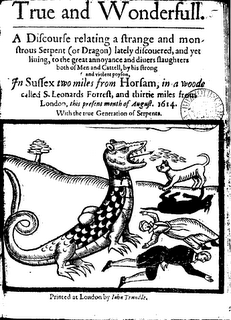

Apart from the animals they knew well, much early modern zoology was suffused with folklore and traditional fantasies. I was reminded of this 'True and Wonderful' discourse of the Sussex dragon by the BBC's notice of the latest investigation of 'Ninki Nanka' in the Gambia - another of those sauropod- survival stories which hinges on tales told by people who knew someone, who knew someone, who definitely saw something one dark night (when he was a boy).

At least nobody is marching off up river in quest this time, the investigation seems to be more into the folklore of the story than conducted with any credulity regarding the creature's existence. See

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/africa/5180404.stm

The pamphlet about the Horsham beast of 1614 is not quite what it seems to be: I claim it as the first occurence of 'silly season' journalism in English. To elucidate, in my youth, when England was a more parochial country, in the high summer, serious news would run thin. Inveterate murderers would go to the seaside with surviving members of their family, bank managers were too busy out on the links to empty the branch safe and flee abroad, trials went into lengthy recess. There was no news, but news had to be found, and so we had 'silly season' stories. In these days of a global news reach, every day brings its bad news, and trivia to all tastes, then, the journalist made the silly season news.

If you read this pamphlet from the silly season of August 1614, you can sub-read the discussion between the hack ('A.R.') and his boss the publisher. There's nothing stirring. But a large snake has been seen on heathland near Horsham. A. R. is told to write it up, despite his protests that their last outrageous stretcher was exploded. The pamphlet shows some of his feelings. He starts off with a semi-apology, to the effect that some recent stories in print were perhaps a product of 'our forward credulity to but seeming true reports' or 'false copies translated from other languages'. But this one is true, he huffs, before signing off his introduction with an ambiguous protest, 'He that would send better news if he had it'.

A.R. then shows off for a few pages, with a gratuitous account of the matings of serpents, and of serpents in history: he is staking his claim to be a real writer and a learned man, far better than this subject allows him to be. Three or four pages of actually relevant material are sandwiched in the middle: it's a serpent ('some call it' a dragon - A.R. seems to mean, people like my get-penny boss here), about 9 feet long, which preys on a rabbit warren in Sussex. It is 'a quantity of thickness in the middest, and somewhat smaller at both ends' (so making it identifiable as a Monty Python). It might have feet, 'but the eye may be there deceived'. It apparently has lumps like footballs on its back, from which its dragon wings may one day grow. A. R. now fibs like the pro he is: it can project venom so far (with two human casualties and two dead dogs already) that no-one can really witness its horror properly and survive. A.R. opines that 'when it shall please God', the serpent will be destroyed, it is rather something to be afraid of in a metaphorical, not literal sense: it is 'to be feared as an eclipse or fearfull comet'.

And he is away again, happy to leave behind this doubtfully veracious subject, and onto the subject of 'serpentine sinnes that live amongst us'. The serpent is an allegory of the corruption of the legal profession, or of drunkards (as it leaves a nauseous mess in its wake). Finally A.R. 'applies' the serpent to 'the Serpentine sisterhood of Brotherly (sic), the diseased Strumpetrie of the Suburbs'. The serpent has a white band round its neck, while you get only 'a white tiffanie about the necke of one of those tugging Gally-slaves of damnation'. There has to be a significant connection there.

And having somehow covered ten pages, he takes his money and runs, while the printer gets a promising boy artist to do the unabashed woodcut that will really sell the pamphlet. It's so good that he puts it in twice.

No comments:

Post a Comment