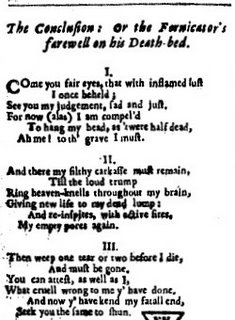

My latest bad 17th century poet is Hugh Crompton (and to say so means starting just like the 'snotty Zoilus' he heared would read his poems). 'O pity, pity him that fryes / Upon the grid-irons of thine eyes' ('The petition') - yes, that bad, but at least he half knows it, and anybody that can conclude one of his books of poetry with a 'Fornicator's farewell' cannot be all bad.

My students are all reading Donne, with various tasks on and about the much-belaboured Elegy 19 in mind, and with much stroking of our chins and shaking of our heads, we will doubtless come to some kind of compromise position between 'Good, but ...' and 'Bad, but ...'

Crompton's merit is that, being a bad poet, you get his feelings straight. The two topics closest to his heart were Venus and Bacchus, sex and drink. Over and over, he returns to having sex with women - poems imagining asking for it, expressing pleasure in it, advising how this end can be achieved ('The Way to Wooe'), and nattering on to women about 'The Mysterie' (my title, perhaps Crompton's best couplet, comes from that poem).

No-one could complain that the women in his poems are excluded from the imaginary conversation - he loves to write a poem that gets right to the point, and then an equally forthright answer (from 'The request to walk'):

... Speak then, where shall we dance a round?

On Sylvan's floor, or Ceres ground?

Or with Priapus shall we play?

Speak now, and chuse the best you may.

The Answer.

The thorny back't and rough Sylvanus

Shall not refresh nor entertain us:

... But 'tis Priapus I desire;

There we will play until we tire.

If we are all set to have a little moral agony over 'O, my America, my new found land', this is Crompton doing woman's body as territory:

Let my hand

Wander along thy unknown land,

To find how well the fruit doth rise,

(As in Canaan Israels spies)

And if the same I do approve,

Therein I'll plant my vine of love

And with a pleasant pain I'le frame

A fertile vineyard in the same.

Come, do not weep; 'twill do thee good

It will refine corrupted blood.

Then struggle not, nor do not shriek,

I have no weapon that can strike

A deadly blow...

At this tender moment, it occurs to him to head off any alarm she might have at the thought of getting pregnant. His poem is called, 'To Caelia, in the fields', and it's the pastoral scene which gives him a useful pointer:

See yon big-bellied ewe, that (late)

Receiv'd the marrow of her mate:

She looks most lovely; so will you

Now you receive your lovers too...

Caelia, perhaps surprisingly, is won by this gallant ovine comparison, and afterwards Crompton, typically, writes her a reply poem, in which she confesses that before 'I abhorr'd / Thy proferr'd love; / But now I see thy spirits, and their energie; / My soul to thee I will resigne'.

'Present your naked bodies unto men' says our poet, in 'To our Mistresses', probably remembering the end of Elegy 19, as he rounds off his set of stanzas with the resounding call to arms (or, a kind of 'Come, madams, come'):

Cast by your blankets once agen,

Present your persons unto naked men.

(cf, of course, Donne's 'cast all, yea, this white lynnen hence ... to teach thee, I am naked first').

But, once again, I don't feel that I have enough in this comparison to get Donne off on all charges. Crompton's amateurishly expressed enthusiasm for getting it on is so endearingly universal (and silly) that Donne just looks 'the worse for being clever', the remark with which a mature student once sank a previous scholarly investigation of the case.

I wonder if Crompton is the first writer to use 'frigidity' with reference to a woman not being interested in sex? The OED indicates that this lamentable sense to the word kicks in early 20th century with Havelock Ellis: "In dealing with the characteristics of the sexual impulse in women ... we have also to consider the prevalence of frigidity, or sexual anæsthesia".

But Crompton, as you'd expect from him, sees such a lapse as only a temporary thing:

So 'tis with my faire Rose, for she

But now ('cause with frigiditie

She's toucht) seem'd dul and dead; but when

Loves spring returns, she'l love agen ('The Comparison').

'Sexual anaesthesia' is not a concept he'd readily have taken on board, I think.

Oh, this is wonderful stuff! Thanks for introducing me to Crompton--I'll have to work in into my lyric class this spring.

ReplyDeleteAh, but what kind of wonderful would that be? But I'm glad that you found him of interest, in one way or other.

ReplyDelete