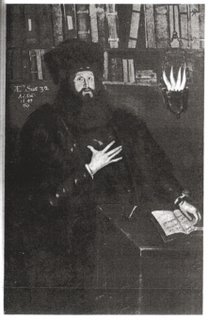

George Daniel, of Beswick (his dates were 1616–1657) vowed that he would never again take razor to his beard after the execution of Charles I. In this self-portrait, he is looking understandably surprised about the immensity of the consequence three years later: he is just 32, but has the beard of a patriarch, which he boldly complements with a balancingly vast furry hat. A friend confronted him with a mirror, and he wrote this poem about his new self:

How am I lost! though some are pleased to say

My mossy Chops estrange

All former Knowledge; and my Brother may,

At distance interchange

Discourse, as to a man he ne’re had known;

It cannot be, persuade

Your Selves; for when you made

Me take a Glass, I knew my Face my own.

The very Same I had three years agoe;

My Eye, my Lip, and nose,

Little, and great, as then; my high-slick't Brow,

Not bald, as you suppose;

For though I have made riddance of that Hair,

Which full enough did grow,

Cropped in a Zealous bow,

Above each Ear; these but small changes are.

For wer't my work, I need not far go seek

The Face I had last year;

The growing Fringe but swept from either Cheek,

And I as fresh appear,

As at nineteen; my Perruke is as neat

An Equipage as might

Become a wooer, light

In thoughts as in his Dress; but I forget;

Or rather I neglect this Trim of Art;

And have a Care so small

To what I am in any outward part,

I scarce know one of All;

'Tis not that Form I look at. Could I find

My inward Man, complete

In his Dimensions! let

Me glory Truth, the better part's behind.

It’s one of Daniel’s better performances. He likes to write about himself, though rather too often about himself as a poet, which he very self-consciously was: I don't know that he is ever really interesting on the topic. He admired George Herbert, but his own verse tends to be chopped-up prose with rhymes. He apparently lost many of his poems in a fire, and probably comforted himself with the assertion that those lost poems were his best ones.

My favourite Daniel piece, though, is his erotic poem about the pleasures of tobacco, which starts:

Come, my Nicotiana; we’ll renew

Our free delights, and Appetite pursue;

Wee fearless will Enjoy those real joys

Lovers would paint, in their fantastic toys…

Normally quite passionless in the relatively few amatory poems he does permit himself, which do conventional 'Platonic'/'Anti-Platonic' topics, in describing his passionate intercourse with the nymph Nicotiana, he really releases the sensualist. Suddenly, our

my free hand

No bashful blush shall ever Countermand,

But in a Thousand forms, thy Tresses part

And slide along, with uncontrollèd Art,

Thy dainty Body; not to fear a frown,

For soiling of thy new white Satin Gown;

My willing Lips shall part, to catch thy Breath,

Sweet, as the Honey-dew, which Hybla hath.

There will I hang; and all my veins inspire

With Ardent Wishes, taken from thy fire;

Hard on my Lips, thy wanton tongue shall press,

And by new Chimistrie in Wantonness,

Send the rich Quintessence of all I seek,

In Dalliance through that faire Alimbecke:

There will I suck, with Cunning Industrie,

Thy Spirits Extracted by Love's Alchimie.

When we 'are be-qualm'd, that long embraces has

Made dull Desire, and wee shall only pass

Faint breathings, I will summon a fresh Store

Of Vigour, far more Active, then before;

And with neat Titillations, new provoke

Decayed fire in thee, to the full Stock;

Invent new postures, & out-doe the old

Fictions, to make 'em Story; when with bold

Uncurbèd flames, we grapple; and not part,

But to renew our Action, and our Art.

I find it hard to think that Mrs. Elizabeth Daniel would not have approved: the oral and semi-tactile pleasures George describes all sound a bit unusual. I imagine that Charles I was a convenient pretext for the vast beard: Daniel clearly liked to be in a nimbus, of hair or smoke: the Creator, whose words issue from a bright cloud or burning bush.