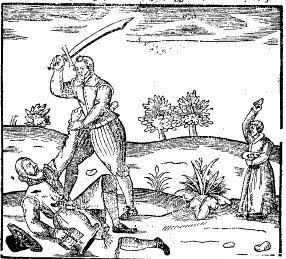

Rape has always been a subject for art, in its most imperially sanctioned form in the various handlings of the Rape of the Sabine women. Lucrece next, and you can add all the mythological victims – Proserpina, Europa, Dejanira, the daughters of Leucippus, Helen, the struggles of the Lapiths and Centaurs. The handling tends towards the queasily sumptuous, even sometimes, with Lucrece, to the tragic.

In the early 17th century poetry of

Stay lovely Boy, why fly'st thou mee

That languish in these flames for thee?

I'm black 'tis true: why so is Night,

And Love doth in dark Shades delight.

The whole World, do but close thine eye,

Will seem to thee as black as I;

Or op't, and see what a black shade

Is by thine own fair body made,

That follows thee where e're thou go;

(O who allow'd would not do so?)

Let me for ever dwell so nigh,

And thou shalt need no other shade than I.

Such poems go into the song books of Henry Lawes, with answer poems of the same kind. Rather more substantially, this is John Collop, ‘On an Ethiopian beauty’, in Poesis Rediviva (1656)

Black specks for beauty spots white faces need:

How fair are you whose face is black indeed?

See how in hoods and masks some faces hide,

As if asham'd the white should be espi'd.

View how a blacker veil o'respreads the skies,

And a black scarf on earth's rich bosome lies.

When worth is dead, all do their blacks put on,

As if they would revive the worth that's gone.

Surely in black Divinity doth dwell;

By th' black garb only we Divines can tell.

Devils ne're take this shape, but shapes of light;

Devils which mankind hurt, appear in white,

When Natures riches in one masse was hurl'd,

Thus black was th' face of all the infant world.

What th' world calls fair is foolish, 'tis allow'd,

That you who are so black, be justly proud.

It was the mention of black patches that set me off on this train of thought. Collop’s poem perhaps develops all the poetry about (native English) women who had the non-regulation black hair, with perhaps a touch of ‘The Song of Songs’ stirring in the writer’s memory.

But Couwenbergh’s painting! I do not think that he was a Dutch Goya, recording horror. He is at best a lumpen type of dauber. The Web Gallery of Art offers his aggressive and beefy Adonis with Frau Venus, and a bad costume drama ‘Samson and Delilah’. His mythological and biblical subjects all look so stereotypically Dutch that he might as well have given them clogs. If he had any aesthetic intention here, it was perhaps a desire to contrast black skin and white, and if this were the case, then he failed his own challenge. Maybe the painting is damaged and overpainted, but the modeling on the black girl fails completely, large parts of her are two dimensional. Her upper body writhes in a horrified attempt to escape, her lower body sits inert. The younger man who has (perhaps) betrayed her to this attack gazes slavishly for approval at the older man, who gloats on behalf of the viewer. The clothed man at the rear is there, it seems, to emphasise that her Nubian or Nigerian blackness is at once funny, and shocking.

The Dutch were building an empire, and this is what empire means: human beings to degrade in play. She is, I take it, a servant (I think she is wearing a maid’s cap). Her unheeded cry of distress will be in the pidgin she has learned to use when meeting other Africans or Asians when out on her errands, a funny Portuguese-Dutch that also makes her suitable for this maltreatment, this palaver.

Who owned this painting, and where did they hang it? How could it have survived so long after its pornographic moment?

It is in the Strasbourg Musee des Beaux Arts, though their website does not draw any attention to it. One of my favourite pictures hangs there: http://www.musees-strasbourg.org/F/musees/bbaa/beauxarts_oc2.html

Nicolas de Largillière, La Belle Strasbourgeoise (1703). Only a small image, there is a better one at:

http://artyzm.com/e_obraz.php?id=950