Two Royal chaplains are buried at the Parish church in Eversley, in Hampshire,

http://www.stmaryseversley.org.uk/

They are Alexander Ross, chaplain to Charles I, and Charles Kingsley (more famous as the novelist and social reformer), but who was chaplain to Queen

I do not know if there has ever been a study of the intellectual mentors of the famous (a mixed history that might start with Seneca’s disastrously temporary hold over Nero). It is hard to imagine that Alexander Ross was anything other than a bad influence on King Charles, for Ross was a cantankerous fanatic, who struck out at any new idea that he encountered. A medieval-style Aristotelian, he attacked Thomas Hobbes, Sir Kenelm Digby, Sir Thomas Browne, William Harvey, and published a late (the last?) refutation of the crazy new (-ish) notion that the earth revolved around the sun, in The New Planet no Planet, Or, the Earth no wandering Star, Except in the wandring heads of Galileans (1646).

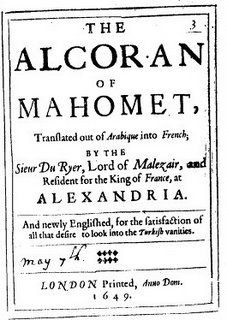

Ross also collected and catalogued religious heretics, and this orthodox man’s obsessive interest in what he saw as the heterodox perhaps led him to some involvement in the first English translation of the Koran. He might in fact have been the translator, the work coming into English via a French translation. The prefatory matter that he certainly did contribute (because he signed it) is a characteristic performance. He knows that the project cannot (by his own narrow principles) be justified, but he also cannot quite resist adding this prize example to his manic collection of (as he sees it) departures from the true faith.

His self-conflict is captured in this passage, from amongst his list of justifications for publishing the work:

“We cannot do better service to our Countrymen, nor offer a greater affront to the Mahometans, than to bring out to the open view of all, the blind Sampsons of their Alcoran, which have mastered so many Nations, that we may laugh at it” (sig d4).

This, of course, casts his Christian readers as the Philistines, foolishly jeering at the undaunted captive who will bring down the roof on them all. Ross cannot quite conceal from either himself or from us his unease about what he is doing. Is he, the staunchest defender of things as they are, introducing the potent force that will demolish everything?

Charles Kingsley was perhaps stranger still. His inner heretic was Darwinian, and he had suffered the full 19th century ‘doubts’, before rallying to settle on his version of manly Christianity. He is buried outside the Church with his somewhat older wife, Fanny, beneath a white cross whose design they had jointly agreed. The inscription reads ‘Amavimus, amamus, amabimus’ (‘We loved, we love, we shall love’). It is more than a piece of Latin declension. When a young woman, Fanny had been drawn to the idea of establishing a Protestant celibate sisterhood. Charles seems to have managed to supersede this with a doctrine in which the orgasm was interpreted as a foretaste of the similar joys of heaven. The immense, almost doctrinal importance he gave to sex as an earthly manifestation of the divine might have made him (in the unlikely case of their consultations ever touching, in some remote fashion, on such matters in a Christian marriage) congenial as a Chaplain to Queen Victoria, who was frisky enough when young. A 20th century memorial window to Kingsley depicts a couple of water babies (I think, though I cannot see that the external gills the story specifies have been included) at either side of St Elizabeth of Hungary, whose status as a married saint made her extremely important to the writer.

But Eversley church takes us back to the Koran again, in a brass memorial plaque to the remarkable Mary Kingsley (Charles Kingsley’s niece). It is a surprise to see in an Anglican Church an inscription in Arabic, even more of a surprise to find that it translates the Koran saying ‘I seek refuge in the Lord of the Daybreak, / From the evil of that which he has created, /And from the evil of the intense darkness when it comes.’ Theologically tough-minded stuff, this: I think only Isaiah 45, 7 is anywhere near as candid in allowing the Bible’s God to be responsible for the whole shooting match, good and bad. One can only suppose that Mary Kingsley was so far off-the-scale in her unconventionality (West African travels, condemner of missionaries, unflinching defender of local customs up to and including slave trading) that they felt they had to rise to the challenge.

History seems to gel, congeal, and aggregate in certain places. The final surprise in

http://www.stmaryseversley.org.uk/Virtual_tour.htm