This will be my last post for a couple of weeks. I am off with my son Tim to America, a first visit for both of us. A fly-drive, with large scenic holes in the ground for me (Grand Canyon, Death Valley), and Las Vegas and Los Angeles for him.

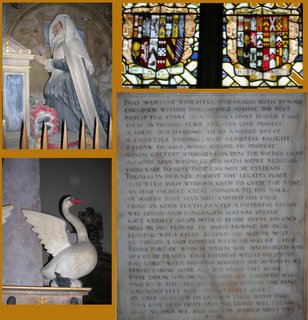

Yesterday, I visited the Church at Bisham Abbey near Marlow, to take a look at the Hoby monuments: Tudor humanism in stone. Elizabeth Cooke, along with her four sisters, was educated by her father Sir Anthony to the highest standards of the age. She married Sir Thomas Hoby, the translator of The Book of the Courtier. He died, as the tomb says, 'at Paris the 13 of May 1566 of the Age of 36 leaving his wife great with child in a strange country, who brought hym honourable home, built this chappell and laid him and his brother here in the tombe together'. Her English verses about him are heart-felt:

Firm in Gods Tryth, gentle and faitheful friend,

Wel lernd and languaged, Nature besyde

Gave comely shape which made ruful his end

Since in his floure in Paris towne he died.

And in her Latin verses, she says he was 'my soul's far dearer part, / Life of my life and solace of my heart ... How happy we then; our wishes, joys the same / one soul inspired our double frame / But ah, how short our pleasures here below'.

The DNB entry on her father describes her as 'formidable'. She became an habitual and angry litigant, while the churchwarden at Bisham repeated to me the local story that she caused the death of one of her children who had raised her ire by (literally) blotting his copy book. There's no record of a missing child, so one has to suspect that her reputation for learning and ill temper caused such posthumous local libels. In her own monument, her will having forsworn 'vain ostentation or pomp', she kneels in a coronet topping an almost Pharonic head-dress of pleated linen, with a full entourage of her children, both living and dead, her elder daughter kneeling before her in her robes as a Countess. A daughter-in-law had the marvellous enamelled glass windows created in 1609, they celebrate the lineage of the families, and were recently restored using a large grant of money from the Glaziers' Company, so precious are they. Margaret Hoby's own monument has the swans, the Hoby's used falcons (or otherwise the 'hobby' hawk) as their heraldic bird. Edward Hoby even named a bastard son he had 'Peregrine Hoby'.

But the main monument is that Elizabeth Hoby made for her husband and his older half brother. It is almost a surprise that the V&A hasn't long ago appropriated something so perfect. In full armour, the two men recline on rush mats, heads on their helms. Sir Thomas' armour is more decorative (if you click on the image to see it enlarged, you can pick up the 'hobby' motifs his suit features), but the modelling (in alabaster) of the faces and hands of both men is very sensitive. Placed together, their being represented at the age they died has obscured the 24 year gap between them, so they have become virtuous Renaissance friends, Protestant champions ('Zealous to God whos Gospel he profest, / When gretest stormes gan dym the sacred light', says Elizabeth's verses, refering to their Marian exile), Pyrocles and Musidorus: the type of male twinning in virtue Jonson praised in his Cary-Morison Ode. There's no sprezzatura here, no 'recklessness' or courtly nonchalance, but rather, a deep Protestant seriousness, and, not suppressed amid the solemnity, the love and bewildered grief of a woman who was clearly not easy to impress.