Back from a stay with my sister. Being praised for eating well is something (lucky) children often experience: my sister always reinstates me in that juvenile role. A near continuous supply of delicious and rich food challenges you to do justice to it. Here at home, mealtimes tend to be interruptions to the business of the day. Particularly under the stimulus of Christmas, my sister makes mealtimes the main daily activity.

I fled (in a way) back here, and soon found myself reading A New and Needful TREATISE of Wind Offending Mans Body (1676, William Rowland’s translation of Jean Feyens’ de Flatibus of 1582). Talk about the hopeless patients of mad doctors! If you tend to wonder whether it is theologians or doctors that have perpetrated the greater accumulation of imposture on humankind, here is the madhouse half way between the two. Via a pervasive confusion about pneumatology, Feyens and his translator confidently treat the wind (flatulence) as a spirit. The wind can therefore be accounted a master explanation for all kinds of physical ills: for instance, toothache is the wind in your teeth; tinnitus is (Chapter XV) when ‘wind gets into the organ of hearing, and sticks there strongly (as by the ringing, hissing, rustling, crackling and murmur is gathered).’ Makes sense to you? A sufferer yourself? Then why not take the cure? ‘Castor and Spike Oyls with Vinegar and Oyl of Roses, do wonders, dropt into the ears, and juice of Leeks with Breast-milk’.

If we can put aside puzzlement about how even the human brain could come up such a concoction as leeks in breast milk, the most invigoratingly bizarre chapter concerns what happens when wind invades the penis. This is Chapter XXVII, ‘Of Priaprismus’. Feyens turns to Galen for clinical experience:

“It chiefly comes to such as dream of Venereal fancies, and the pain is like the Cramp; for the Yard is as in a convulsion, being pufft up and stretched, and they dye suddenly except cured.’

As this is a condition of acute emergency, and if we do not have Shakespeare’s Marina around to radiate a quenching chastity (‘Shee’s able to freeze the god Priapus, and vndoe a whole generation’), then we must undergo the cure:

“Therefore against the pain and inflammation, presently open a Vein, and use a small Diet three dayes, and foment the parts about, and the Yard, with Wool dipt in Wine and Oyl: give a gentle Clyster not sharp and feed him with a little Corn and Water. If it last long, cup and scarifie: if there be much blood, use leeches to the part, and cataplasms of Barley flour: loosen the belly with Beets, Mallows, and Mercury boiled … Lay Coolers to the Loyns, as Nightshade, Purslane, Houseleek, Henbane. Let the space between the Fundament and the Yard be cooled with Litharge of Silver, Fullers Earth, Ceruss, Vinegar and Water … He must lye upon one side, and lay under him things against the emission of Sperm: And he must see no Venereal pictures, nor hear no wanton discourse”.

I’d think a medley of boiled mercury, hallucinogenic plants and applied leeches would more than do the job. Pursuing these inquiries into past delusions, I didn’t know whether I was pleased or alarmed to find myself working the same side of the street as the doctissima Professor Steven Connor, who here writes with a broad imaginative vision of the body, including his own, envisaged as a series of (windy) vacuities:

http://www.bbk.ac.uk/english/skc/vapours/

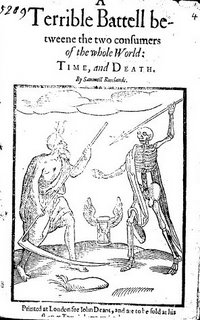

The never-failing internet allows you to peruse a 1592 copy of de flatibus humanum corpus molestantibus (I guess that my learned colleague found the shorter title, de Flatibus, irresistibly Rabelaisian). The images 200-202 give the pages concerned with priapism, and demonstrate that Rowland’s translation was very close.

I was interested to see that the publishers of Rowland's translation end the volume with a list of the texts Billingsley has for sale and the salves, pills, elixirs and sympathetic powder he also kept in stock. I am going to tell my pharmacist friend that he must negotiate a commercial tie-in, sharing premises with Waterstones.