…That both of them coming to the said Copse about 9 of the clock in the morning, the said William Aven took the sword, and laid it down neer the place, as this relatant was directed by the said Apparition; and both of them turning about to come away from thence, this relatant looking back saw the Apparition in like habit of cloth, as aforesaid; which when this relatant discovered, he said to his brother-in-Law, Here is the Apparition of Father; but he said, I see it not; so this relatant falling on his knees, praying to God to preserve them both, asking his said Brother in law whether he did see it, who said, No; and then he said, Lord open his eyes, that he may see it; who then replyed, Lord grant that I may not see it, if it be thy blessed will; & then the Apparition beck’ned his hand to him to come to it, & this relatant then said, In the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost what would you have me to do? And the Apparition said to this relatant, Thomas, take up the sword and follow me, & this relatant said, Should both of us come, or one of us, to which it said, Thomas, do you take up the sword, so this relatant took up the sword, & the Apparition went on before him further into the Copps-Wood about 20 lugs [same as a pole or perch, 16½ feet]; & this relatant stood about a lug and a half from it, his said Brother standing neer the place, where he first laid down the sword, & this relatant laid down the sword upon the ground, & saw something like a Mastiff-Dog of a brown colour, and the Apparition waving towards this relatant, he stepped back about 3 steps, & the Apparition said, Do not be afraid Thomas, for I have a permission for to reveal things unto thee, but have a Commission not to touch you; & when it had taken up the sword, & went back to the place at which before it stood, when this relatant saw the Mastiff-dog which as before, the Apparition pointed the top of the sword into the ground, & said, In this place lyeth buried the bones of him that I murthered in the year 1635, which are now rotten and turned unto dust…

We are in Wiltshire in 1674, on the road between Marlborough and Alton Barnes.

http://www.multimap.com/maps/#t=l&map=51.39027,-1.81467|16|8

(keep the map centered, switch to ‘aerial view’, then go to zoom factor 16: you should have the only wood on the Marlborough-Alton Barnes minor road, shaped like a broken U. That’s Shaw House, near the site of the lost village of Shaw. Work south along the road for the White Horse on the downs. My image is the Google Earth one.)

The copse is (I surmise) now called Boreham Wood. It’s a landscape so rich in history as to be faintly spooky still. Just to the south is ‘Adam’s Grave’, and an associated assembly of barrows, tumuli, encampments. The famous ‘Led Zeppelin’ Alton Barnes crop circle (which I visited, paying 50p to wander round it at field level) was a kind of tribute to that quality of mystery.

http://www.lucypringle.co.uk/photos/1990/uk1990bi.shtml

Our bucolic Hamlet is in fact a son-in-law, Thomas Godard, ‘a Man of good Understanding, Honest Life and Conversation’, an illiterate weaver. His dead father-in-law started appearing to him on November 9th, when Godard was delivering serge to a man in the village of Ogbourne St Andrew, north of Marlborough. Suddenly, at a stile, he saw his late father-in-law, who had died the previous May, and who ought to have been in his grave in Marlborough. ‘I perceive you are afraid, I will meet you some other time’, said the ghost, but it hardly made things easier to bear by surprising his son-in-law at his loom that same evening at seven, when it lifted ‘the lid of his window’. Thomas rushed out in terror. It was even worse the next night: ‘after this relatant went forth into his back side about the same hour with a candle in his hand to make water, and as he was so doing the like Apparition came round his Wood house, and this relatant also being in a fear and his Candle waxing out, he ran into his house.’ Joseph Glanvill, retelling the story almost verbatim in Sadducisimus Triumphans (1681), part two, relation IX, leaves out the homely motive for the trip outdoors. On the succeeding Thursday, as Goddard was coming back from Sir Bulstrode Whitelock’s house in Chilton, and was passing near Ramsbury manor house, a hare caused his horse to rear up and throw him. He got up to face his late father-in-law once again: ‘Thomas you have tarried long’.

This time the impatient ghost imparted its full requirements: Thomas is to tell his brother-in-law William to bring the sword he inherited to that wood at the roadside ‘as we go to Alton’. The ghost reinforces the message: ‘he never prospered since he has had the sword’. Will is also to give some 20 shillings to his sister Sarah, while Goddard himself is to pay off a debt that Aven had denied in his lifetime.

Godard told his story to the mayor of the town and others: they advise him to order William Aven to take the sword to the copse where the last part of the drama will be played out. Which is where I began.

Interpretation 2007:

I think we can see what was going on. Goddard has married into an unhappy and divided family. Avon had fallen out with and disinherited one of his daughters on her marriage (Sarah). Goddard’s wife Mary, the ghost says, ‘is troubled for me, but tell her that God hath showed mercy to me beyond my desarts’ – so the ghost announces at their first meeting, amid the catching-up conversation between the dead man and the living (‘How do Will and Mary? … what? Taylor is dead…). Even in his account of this first meeting Godard is shaping up to getting the family to put right the wrong Avon had done to their newly widowed sister, Sarah Taylor. He says that the apparition held out a hand, with twenty or 30 shillings in silver in it, to be given from the dead Avon to the daughter he’d quarrelled with on her marriage. But Godard did not dare take money from the ghost: he wants the family to do this, his wife and her brother to relent.

The dead father was clearly a man with a temper, a known owner of sword. His daughter Mary (as Godard her husband knows) fears that he may be in hell. His son Will is not making a go of things, but has hung onto the sword, which feels to Godard like a promise of future trouble. He wants to get the sword off his brother-in-law.

And so Godard imaginatively brings the dead man back to earth, a troubled ghost (but not damned). He does not think anyone will protest against the notion that Avon had been a denier of his debts, a thief and a murderer. His brother-in-law cannot see the ghost, but did say he heard sounds like words, but he could not make them out. The ghost himself underlines that his victim has long turned to dust, so there is no point digging where Godard alleges that he could see a bare patch of sunken earth shaped like a grave. No-one is meant to ask the name of the victim, the former owner of the sword: it is not his function to be investigated, he is being invented to lift Avon’s influence over Will and Mary by blackening his character while at the same time righting his more minor (but real) wrongs (to Sarah, and some other small debts and legacies). The hare and the mastiff dog are diabolic creatures, and Avon becomes for the pamphlet “the deemon of Marleborough”: but Mary has to know that God has spared him despite it all.

Godard told this elaborate story to exorcise the bad feeling the father had left in the family. I suppose it was produced in him by family pressures real enough to make him credible, even to himself. But he told it rather too well. It took some pressure to get the brooding William to give up that dangerous sword: the mayor and town elders are behind Thomas’s ordering of him to that lonely roadside wood. Thomas needed a community of believers: but they took up his story. He wanted the ghost laid (“Vanished out of his sight, and he saw it no more”), but, as people will do, what they’ve heard someone say he can see, they claim that they can see it too: “Sir, This is to Certifie you, that Edward Aven doth still appear, and shews himself to several people … and in the same Cloaths, which he wore in his lifetime; as a long White-Crown’d hatt, Blew Cloaths, and White Stockings: All this Last Week he was seen.” Not only are other people seeing Avon, but (as the later investigation of the case in Joseph Glanvill says), the Mayor of Marlborough, mixing credulity with pragmatism, has the ‘grave’ Godard designated dug up: there was nothing there, of course.

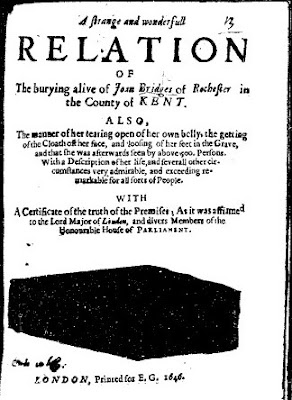

The deemon of Marleborough, or, More news from VVilt-shire in a most exact account of the aparition of the ghost, or spirit of Edward Aven : published heretofore, but now much augmented, with many more discoveries, containing wonderful passages, from its first appearance there, to the 24th of Jan., 1674/5 : being the examination of Thomas Godard, the said Avens son in law, taken before the major, and other magistrates of that borough., [London : s.n.], 1675.

I append, just for interest and contrast’s sake, the examination of this case given in Joseph Glanvill’s Saducismus triumphatus, or, Full and plain evidence concerning witches and apparitions in two parts (1681). Glanvill died before he had his treatise ready for the press, his posthumous editor seems to have added these commentaries. Glanvill and his editor (who completed the book from papers Glanvill had left behind) are predisposed to believe in any supernatural manifestation, as part of their rearguard action to keep up the fading belief in witches.

“That Tho.Goddard saw this Apparition, seems to be a thing indubitable; but whether it was his Father in Law's Ghost, that is more questionable. The former is confirmed from an hand at least impartial, if not disfavourable to the story. The party in his Letter to Mr. G---writes briefly to this effect. 1. That he does verily think that this Tho. Goddard does believe the story most strongly himself. 2. That he cannot imagine what interest he should have in raising such a story, he bringing Infamy on his Wives Father, and obliging himself to pay twenty shillings debt, which his poverty could very ill spare. 3. That his Father in Law Edward Avon, was a resolute sturdy fellow in his young years, and many years a Bailiff to Arrest people. 4. That Tho. Goddard had the repute of an honest Man, knew as much in Religion as most of his rank and breeding, and was a constant frequenter of the Church, till about a year before this happened to him, he fell off wholly to the Non-Conformists.

All this hitherto, save this last of all, tends to the Confirmation of the story. Therefore this last shall be the first Allegation against the credibility thereof. 2. It is further alledged, that possibly the design of the story may be to make him to be accounted an extraordinary some-body amongst the dissenting party. 3. That he is sometimes troubled with Epileptical fits. 4. That the Major sent the next Morning to digg the place where the Spectre said the Murdered Man was Buried, and there was neither bones found nor any difference of the Earth in that place from the rest.

But we answer briefly to the first, That his falling off to the Non-Conformists though it may argue a vacillancy of his judgment, yet it does not any defect of his external senses, as if he were less able to discern when he saw or heard any thing than before: To the second, That it is a perfect contradiction to his strong belief of the truth of his own story, which plainly implies that he did not feign it to make himself an extraordinary some-body: To the third, That an Epileptical Person when he is out of his fits, hath his external senses as true and entire, as a Drunken Man has when his Drunken fit is over, or a Man awake after a night of sleep and dreams. So that this argument has not the least shew of force with it, unless you will take away the authority of all Mens senses, because at sometimes they have not a competent use of them, namely in sleep, drunkenness or the like. But now lastly for the fourth which is most considerable, it is yet of no greater force than to make it questionable whether this Spectre was the Ghost of his Father, or some ludicrous Goblin that would put a trick upon Thomas Goddard, by personating his Father-in-Law, and by a false pointing at the pretended grave of the Murdered make him ridiculous. For what Porphyrius has noted, I doubt not but is true, That Daemons sometimes personate the Souls of the deceased. But if an uncoffined body being laid in a ground exposed to wet and dry, the Earth may in 30 years space consume the very bones and assimilate all to the rest of the mold, when some Earths will do it in less than the fifteenth part of that space: Or if the Ghost of Edward Avon might have forgot the certain place (it being no grateful object of his memory) where he buried the murdered Man, and only guessed that to be it because it was something sunk, as if the Earth yielded upon the wasting of the Buried body, the rest of the story will still naturally import that it was the very Ghost of Edward Avon. Besides, himself expresly declares, as that the body was Buried there, so that by this time it was all turn'd into dust.

But whether it was a ludicrous Daemon or Edward Avons Ghost, concerns not our scope. It is sufficient that it is a certain instance of a real Apparition, and I thought fit as in the former story, so here to be so faithful as to conceal nothing that any might pretend to lessen the credibility thereof. Stories of the appearing of Souls departed are not for the tooth of the Non-conformists, who, as it is said, if they generally believe this, it must be from the undeniable evidence thereof nor could Thomas Goddard gratifie them by inventing of it. And that it was not a phansy the knowledge of the 20 Shillings debt imparted to Thomas Goddard ignorant thereof before, and his Brother Avon's hearing a voice distinct from his in his discourse with the Apparition, does plainly enough imply. Nor was it Goddard's own phansy, but that real Spectre that opened his shop-window. Nor his imagination, but something in the shape of an Hare that made his Horse start and cast him into the dirt; The Apparition of Avon being then accompanied with that Hare, as after with the Mastiff-Dog. And lastly the whole frame of the story, provided the Relator does verily think it true himself (as Mr. S. testifies for him in his Letter to Mr. Glanvil, and himself profest he was ready at any time to swear to it) is such, that it being not a voluntary invention, cannot be an imposing phansy.