I read James Serpell’s piece on familiar spirits,

‘Guardian Spirits or demonic Pets: The Concept of the Witch’s Familiar in Early

Modern England, 1530-1712, which appeared in Angela Creager and William

Jordan’s The Animal/Human Boundary:

Historical Perspectives (2002). It’s a thorough job, with some very good

quotations and a jolly chart of the various animal forms the devil was said to

have adopted.

The sources of bemusement remain: where such a

strange idea came from, and in particular why it was English witchcraft that so

featured the diabolic familiar in animal form.

It’s useful first to remind oneself of a widespread

psychological phenomenon:

The Wikipedia writers paraphrase from Klausen and Passman, ‘Pretend companions

(imaginary playmates): the emergence of a field’ in the Journal of Genetic Psychology (2006): “Adults in early historic

times had entities such as household gods and guardian angels, and muses that

functioned as imaginary companions to provide comfort, guidance and inspiration

for creative work.”

After a non-Christian origin, a conceptual and etymological

inevitability operated to produce the familiar spirit in animal form.

In Roman times, Ronald Hutton explains, you had a lares familiares, a guardian angel

called your genius (a woman might

have referred to hers as her natalis Juno). On your birthday, you made special

vows and little sacrifices to your genius

or juno on the household shrine, the lararium. Emperors, meanwhile, had a numen, and their re-union with their numen at death was what made a dead

emperor into a god. Evil spirits, says Lemprière, were the Larvae or Lemures. They

were considered to be the spirits of the dead, and ceremonies, Lemualia, were performed to keep them in

their graves or make them depart. These evil spirits are just a general

supernatural nuisance; they are not assigned to living individuals as opposites

to the genius.

The genius is

considered by some lexicographers to link to the word jinn. In Moslem tradition, Jorge Luis Borges explains, Allah

created three forms of intelligent beings: angels, from light, the jinn, from fire, and humankind, from

earth. The jinn can be evil. They

manifest, Borges reports his sources as saying, first of all as clouds or

undefined pillars, then can stabilise or condense into a human or animal form,

as jackal, wolf, lion, scorpion, or snake – definitely not as domestic animals.

Jinn can overhear angelic

conversations, and so pass on second hand vatic information to wizards. But the

harms attempted by an evil jinnee are

easily defeated by invoking the name of Allah, the all Merciful, the

Compassionate.

For the European tradition, the OED’s etymologies

take the story forwards. In post-classical Latin of the 12th

century, the guardian angel is the angelus

familiaris. Because the culture was Christian, and that culture was intensely

given, after Prudentius’ hugely popular 5th century Christian poem,

to analysing the psychomachia, the

battle happening in and around an individual soul, familiar devils followed,

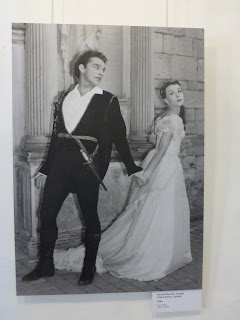

c.1464. You now have both a Good and a Bad Angel, like Faustus, and they form a

morally effective pairing, as in this illustration:

A court scene, with the person testifying between

his evil and good angels.

From Ulrich Tengler, Der neü Leyenspiegel (Strassburg, 1514)

https://www.flickr.com/photos/yalelawlibrary/11734629074/in/album-72157639358477444/ (See folio CXXXV).

The OED assigns spiritus

familiaris to the 15th century, and has the term in its English form from

1545. EEBO can be used to add further quotations. The “familier spirit of a

mannes awne minde” is mentioned quite neutrally in the translation of Erasmus’

commentary of Cato’s precepts in 1553, while 1554 provides the more opprobrious

“one that had a familier spyrit, and used enchauntry” in a work by Richard

Smith.

Of course, the neutral use is in commentary on a

Roman writer. In the context of magic, the familiar spirit may have set off

like the daemon of Socrates, being the source of your knowledge. But when that

knowledge was forbidden, no neutral ‘daemon’ is possible: it is a demon

informing you (or, more likely, misinforming you).

Lurking in familiar

was a connection to the house: Latin, familiaris,

‘of a house, of a household, belonging to a family, household, domestic,

private’. Canis familiaris is the

domestic dog.

The Roman lares

familiaris or penates were

represented in the form of dancing human-shaped figures, who carry a libation

cup and dish. But when the familiar spirit is no longer a daemon but a demon, no longer a genius

but an evil genius, a witch-hunter

can infer that, as it would be instantly incriminating to have a largely

human-shaped devil visible in the household, the devil is going to be present either

invisibly, or disguised in animal form.

Genesis, as it had been interpreted from the second

century, gave ample warrant for Satan assuming animal form. Nobody could

imagine Jesus appearing to them in the form of a dog, but part of satanic

debasement was non-angelic form. Milton has his Satan suavely passing from

cormorant, to tiger, to toad, to serpent, as best serves his advantage.

Intelligent writers of Genesis-based poems, like Du Bartas and Milton, were

fascinated in just how Satan could get a snake to speak. Du Bartas even seems

to imagine that one way round this difficulty is that Satan, invisible, is

‘playing’ the serpent, like a brilliant musician coaxing a good sound from a

poor musical instrument (Sylvester, translating Du Bartas, interjects an

allusion to John Dowland’s ability to coax harmonious music out of a

broken-down old instrument).

|

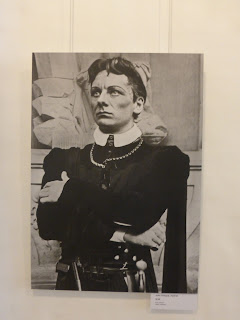

| Imputed 'devil's door', Warfield Church, Berkshire |

I think that the medieval church in general

down-played the genius or ‘good

angel’. They are mentioned, but really they occupied a role the church wanted

for itself: leaving aside special miraculous interventions by the Blessed

Virgin Mary, the church is the best protector. Having promoted itself to

guardian-angeldom, the church would naturally incline to emphasise what you

were being so well protected from. As an instance, on the Heritage Open Day

this last weekend, I cycled to Warfield Church in Berkshire, which has one of

the reputed ‘devil’s doors’. It is asserted that such small doors, in the North

wall of a church, were opened during the medieval Catholic baptismal rite –

involving exorcism – of a baby in the font placed near to the devil’s door.

Subsequently, ‘devil doors’ tended to be walled up: in the Reformation, it is

said. Maybe very early Christian buildings had a North-side door for the

not-yet baptised, and the feature was reproduced in later buildings. An exorcised

devil flying out of an aperture is such a common motif that such doors probably

did at some later time have that different function in a drama of exorcism

(absurd though it is for a spirit to require a doorway). This is a separate

issue; my point is about the church’s tendency to make the devil familiar. The

devil was inside you prior to your baptism, and he is always trying to resume

control, he will always be close at hand.

Once the devil had become multiplied into vast

numbers of evil spirits, every sinner can have one, and the church can busy

itself beating them away. Some irremissible sinners, demonology began to say,

struck personal covenants with devils. Invisible devils inevitably had a

neither-here-nor-there quality. It became the duty of the person accused of

witchcraft, or the person who said they were bewitched, to see devils. Particularly in England, and perhaps because the

English always seem to have accommodated an odd range of animals living with

them, animals already in the house were co-opted as devils; or in the absence

of animals, the assumed attendant devils were assigned animal forms by those

who claimed to be witnesses, or by witches who were trying to confess compliantly

enough to worm their way back into judicial favour.

The sinister, vice, element from psychomachia had in effect combined with

the household suggestions of ‘familiaris’

(“some domestical or familiar devil” in Daneau, A Dialogue of Witches, 1575) to suggest that the spirit prompting

to evil adopted disguise as a domestic animal, as when Elizabeth Stile

confessed that when she went to gaol, “her Bunne or Familier came to her in the

likenesse of a black Catte” (1579). The OED does not include this sense for the

noun ‘bun’, but it was in regular early modern use, alongside ‘imp’, as in Great News from the West of England: “In

the Town of Beckenton … liveth one William Spicer, a young Man about

eighteen Years of Age; as he was wont to pass by the Alms-house (where liveth an Old Woman, about Fourscore) he would

call her Witch, and tell her of her Buns; which did so enrage the Old Woman,

that she threatened him with a warrant…”

If the church had appropriated the role of good

genius, we can then see Milton’s Comus as

powerfully re-instating the guardian angel, the daemon, sent direct from heaven

to intervene - because Milton was well on the way to his repudiation of

organised worship.

I think the most revealing familiar spirits are

those whose forms and actions are recounted in Edward Fairfax’s Daemonologia. I say this because Helen

Fairfax, the writer’s eldest daughter, was simply making them up, deliberately

and in a calculated fashion, to get her father’s attention. Yes, reported

familiars were always made up, but in this case there’s no ambiguity about

delusions, or hysteria, or deception by a third party. Helen Fairfax simply let

rip, unleashed her imagination and expanding on themes she’d heard in other

reports.

She witnessed a Protean devil: human formed, then a

beast with many horns, then a calf, then “presently he was like a very little

dog, and desired her to open her mouth and let him come into her body, and then

he would rule the world”

Her father is completely credulous. On the 16th

November, 1621, a black dog, she said, had leapt onto her bed “and I tried if I

could feel the dog, but I felt nothing; and the wench said ‘The dog has leaped

down and gone’ ”

Then there is Margaret’s Wait’s alleged familiar “At

last the woman pulled out of a bag a living thing, the bigness of a cat, rough,

black, and with many feet”. This alarmingly non-tetrapodic beast keeps trying

to sit on the Bible Helen is conspicuously attempting to read.

More imaginative is the black cat: “when the cat

opened her mouth to blow on her, she showed her teeth like the teeth of a man

or woman”. This imaginary being mixes together the devil in animal form and the

witch who, in her animal form, is incompletely transformed.

The women that Helen Fairfax so heedlessly accused

were taken for examination. No supernumerary teats were found on them, and they

were acquitted when tried. The relentless Helen, who is making all this up,

subsequently sees a witch breast-feeding

her familiar, and is indignant at this crafty way of escaping exposure. She has

come up with a way the women at the York assizes escaped proper detection.

Finding her lies officially disbelieved only caused Helen to rally with more

lies.

What moved Helen Fairfax was said to be paternal

neglect. She maybe also took some pleasure in deceiving a father who had no

regard at all for her intelligence. A desire to be married and away from home

is also apparent. Satan appears to her as a gallant gentleman. The God himself

appears to her in the hall. This is too much for the family, who can believe in

the devil being present, but not God himself, and Helen swiftly adjusts her

story, as the God who appeared to her produces evasive answers, and finally

shows his horns.