Richard Saunders was one of those astrologers who published an annual almanac, and I suppose that back in those days of almanac buying, you found a style of almanac that suited you, in the range between the dryly factual and the apocalyptic, and stuck with the writer, or his ghost writers, year after year.

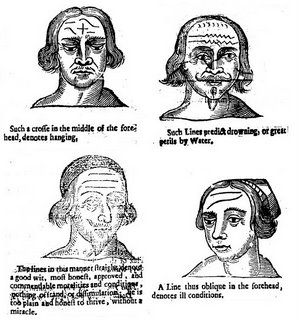

Saunders had a side line in palmistry and physiognomy (metoposcopy is his favoured term for what he does), and between 1663 and 1676, his major work in this area acquired increasing numbers of illustrations. I have grouped seven of them into the two jpegs above. The semiotics of the face can read simplistically: straight lines across the forehead meaning plain and honest, oblique lines in an asymmetrical countenance, bad behaviour. If you have wavy lines, fear death by drowning, and a cross in your forehead gives you the Tyburn mark, and your destiny is to be hanged. Others are quite capricious and opaque - a line with a wart predicting dangerous falls (plural!) from high places.

My puzzle for anyone looking at this posting, is who was the man at the bottom right? Here, Saunders shifts from invention of typical faces to including the face of a real man: 'an excellent man' but 'mightily tost on the waves of misfortune' 'When by the Divine Grace and favour, he seemed to arrive safe at his haven of rest ... he was beyond expectation, by the contrary tempest of adverse fortune, again hurried into the depth of perplexities'. Clicking on the image gives a larger jpeg, of course.

Saunders added 'A Treatise of the moles of the body of man and woman', offering 'Rational Judgements by the moles of the body'. The discussion begins with a facial chart, for Saunders asserts that (something like acupuncture or reflexology), a mole in a particular part of the face will always have a corresponding mole on some part of the body. According to the places, Saunders lets his reader know which star governs the person so marked; while the shape and colours of the mole add levels of meaning. As ever, men have more forms of destiny open to them, while the female destiny often comes down to her marriage, chastity, and the like. Thus, a mole in the middle of the forehead under the lines of the sun (formula 18) 'shews a man to have a great voice, to be a good Oratour, yet luxurious and addicted to gluttony' while in a woman the same mole 'denotes a woman given to lust and lascivious courses'. As with any fortune-telling, predictions of wealth and status are important. A mole on the right side on the end of the line of Mars 'prenotes a man to thrive by Playes' - unless it happens to be black, when 'let him avoid Playes'. Nothing so complicated for women: 'it signifies Inheritance from Parents.'

All bizarre and arbitrary, but I can imagine his system being revived tomorrow. All this talk of moles reminds me of Donne, in Elegy 18:

her Chin

Ore past; and the streight Hellespont betweene

The Sestos and Abydos of her breasts,

(Not of two lovers, but two loves the nests)

Succeeds a boundless sea, but yet thine eye

Some Island moles may scattered there descry...

No amount of anguishing about woman as territory, reification and the rest, will ever quite get me to relinquish these lines as true to erotic experience. Saunders sticks chastely to the face, and simply says that a mole on the body will be present if there is one in some part of the face. Where would romance plots have been without these 'blots of Nature's hand', which individuate and indentify people as securely as fingerprints. Iachimo spies Innogen's 'mole cinque-spotted', and tortures Posthumus with the lie that 'By my life, / I kiss'd it', as the little mark of melanin hovers between embellishment and blemish. But I am wandering from my subject.

1 comment:

'He never seems to see beyond that' (the female form), interjects Phoenix. Might make a good essay subject. But however reified Donne may make women in his poems, they engage intensely with what the women they invent are thinking (That 'Except she meant ... what ere shee meant' note). Not that this makes them any less provocative!

As for reply poems, the indignant 'Philo-Philippa', writing her commendatory poem on Katherine Philips, is probably about as near as you will get, and Margaret Lucas mocks Donne as 'Dr Costive' in 'The Comical Hash'. In Tudor court poetry, there's far more of a sense of male-female dialogue (I mean in the Wyatt circle, or Anne Vaux writing to the Earl of Oxford). But in the end, wouldn't any woman writer answering Elegy 18, or the other elegy you mention, have had an agenda set for her? A. L. Rowse egregiously co-opted Emilia Lanier's poems as 'The Poems of Shakespeare's Dark Lady', making them into an adjunct to an ill-founded theory about Old William: let's not go the same way. (Maybe this is just my sneaky way of trying to leave a space in which Donne can continue to be done). But thanks for being interested. Roy.

Post a Comment