This week, a piece of mild Restoration era smut, delivering something rather less strong than the title promises. The ballad deals with a marriage contracted between two women, Susan, who dresses like a man to woo Sarah, who is delighted to have such a beautiful gallant as her suitor, marries in haste, and then is disappointed on the wedding night.

More comment below the text, which I have slightly tidied up in spelling and punctuation.

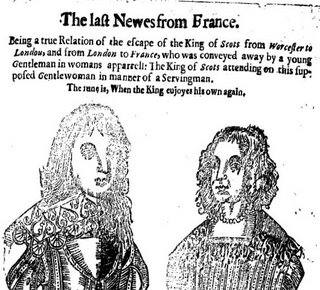

Cheat upon Cheat, OR, The Debaucht Hypocrite.

Being a True Account of two Maidens, who lived in London near Fish Street, the one being named Susan, the other Sarah. Susan, being dressed in Man's Apparel, Courted Sarah, to the Great Trouble of the deceived Damsel, who thought to be pleasured by her Bridals Night's Lodging, as you may find by the sequel.

When Maidens come to Love and Dote.

And want the use of man,

Against their wills they needs must shew't

Let them do what they can.

To the Tune of, ‘Tender hearts of London City’.

Come and hear the strangest Story,

Ever Fortune laid before ye,

of a wedding strange but true,

For such a one was never known,

as I will now declare to you.

There was two maids in London City

One was wanton, t'other witty;

Sue and Sarah were their Names,

It doth appear they married were,

and Sarah tasted Cupid’s flames.

A Gentleman that lived nigh 'um,

Had a mighty mind to try 'um,

and this Susan did engage,

That she would go and court her so,

that she her passion might assuage,

Disguised went she, and fell to wooing

Sarah she would needs be doing,

so she quickly gave consent,

They soon agreed to match with speed,

but now poor Sarah doth lament.

Susan strangely was disguised,

Sarah’s heart was soon surprised,

so that she did condescend,

She ne'er denied to be a Bride,

but her young Lover did commend.

While her joys were thus completed,

Sarah was extremely cheated,

which did make her vitals fail,

To bed they went with joint consent,

and she found a cat without a tail.

Now is Sarah much concerned,

But by this some wit she learned,

though she for it paid full dear,

For from her eyes, with fresh supplies,

down trickles many a brackish tear.

Sarah thought love her befriended,

Tho’ but mark what this attended,

and twill make you much admire,

That Susan she, so arch should be,

to set poor Sarah’s heart on fire.

With sword and wig was Susan dressed

Sarah thought that she was blessed,

with a gallant none more fair,

But pity 'twas, a wanton lass,

should be so much mistaken there.

Now is Sarah discontented,

Her misfortune much lamented,

Maidens then pray have a care,

Lest Susan comes with sugar plums,

to bring poor damsels into a snare.

Quoth Sarah ‘Why would you abuse one,

Whom you loved, deceitful Susan,

why would you me thus betray?’

‘Oh’ then quoth she, 'twas jollitry,

that made me thus the antic play.

Let no one know how you miscarried,

How mistaken when you married,

for twill make the world to laugh,

You walked your round, and then you found

a constable without a staff.’

Wonder not why this I write you,

To be merry I invite you,

and to none I harm do think,

Let Sarah grieve, Sue did deceive,

which made poor Sarah’s heart to sink.

To all Maids let this be a warning,

All are wise that still are learning,

Beauty is a mere decoy,

Then have a care, least Cupid's snare,

do make you curse the blinking Boy.

Printed for J. Blare, at the Looking-Glass in the New-Buildings on London-Bridge.

Not a sophisticated performance, and written for unsophisticated readers - men, men who want to feel part of the libertinage and sexual knowingness of the era. The narrative stutters badly over the wooing/wedding night, which one would have thought a simple sequence to describe.

The superfluous parts of the narrative are revealing: that the inception of Susan's deception comes from a man, glancing at the literary motif of 'trying' a potential partner before making a final choice to commit. But this third party is quickly forgotten, once he has served his function of removing the possibility that one woman might want to try sex with another woman.

The message of the rest of the ballad is to reassure the reader that women may indeed be beautiful (so a woman dressed as a man makes a very winning gallant). But, lacking a penis, such a wooer will only disappoint a woman, being a cat without a tail, a constable without a staff, etc.

Who would have predicted that? Susan is a cheat because she's not a man; Sarah, surely cheated rather than cheating, can only be another cheat because she deserts true masculinity (ugly-faced but virile) with such rapidity in her haste to marry her (female) gallant. Imaginary female readers, 'Maids', are solemnly warned that Susan may still be out there, alluring young women with sugar plums rather than testicles.

I suppose pornography, smut anyway, must always have a large element of the naive about it.