It’s life as we know it, Tim!

A review of One More Kilometre and We’re in the Showers: Memoirs of a Cyclist by Tim Hilton (Harper-Collins, 2004) (£16.99 hb, pb edition forthcoming).

Here’s the book the regular ‘Less about Lance, please’ correspondents of Cycling Weekly would certainly relish. Just two passing mentions of the American (and those merely in lists of names), similar short thrift for that conspicuous mismatch between achievement and personality, Miguel Indurain, and no space at all for that talent increasingly interesting in its failure of fulfillment, Jan Ullrich. Here, instead, are two of Tim Hilton’s keynotes: “a club cyclist … by this term I mean someone who is dedicated to the culture of the bike, as well as being a member of a club” (p.8). And, “cycling is not merely about physical pleasure. It is also about knowledge and living memory: the memories we can share with those who are still alive” (p.64). This nostalgic, highly personal account of a life-long preoccupation with the bike inevitably reflects the professional racing scene, but only as it has swayed his particular imagination over the years. That his hero was Fausto Coppi leads him to make, without parading any such intention, a persuasive case that this was the greatest cyclist of all time. Anquetil is there, but really only because he had the good sense to learn from Coppi. The Reading CC chairman saw Coppi at Herne Hill (this was the 14th September, 1958, Hilton says), and still describes with relish the sound of Coppi’s tyres swishing under the impetus of the supple, powerful pedal-stroke described here. At that moment of communion (did the whole stadium relish that same acoustic pleasure, as it is a sound eloquent to any practised rider?), Hilton too was of course present.

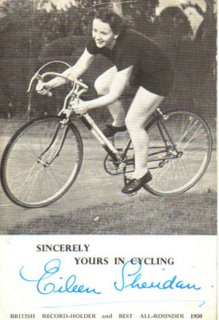

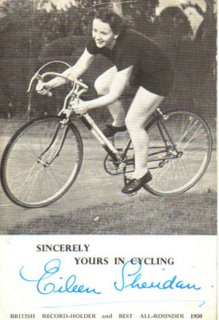

Hilton loves most the riders whose characters he can describe: Louison Bobet’s long road to the top, the bloody-mindedness and finagling of Reg Harris, Alf Engers ‘white-lining’ his way to the first 30mph 25 mile Time Trial, the gregarious Ray Booty serving out bacon and eggs for the also-rans at his primus stove after another triumph. Veterans and ladies are as celebrated as any famous male riders riding in their prime. A marvelous chapter on the delightful and valiant Eileen Sheridan, hallucinating her way through the last agonies of her 1,000 mile record after setting the end-to-end, while her supporters wept, sang, ran alongside (even proposing to her!), is complemented by a respectful but rather head-shaking account of the extremist Beryl Burton at work (rhubarb-forcing, it seems – from what one reads, after Beryl Burton and her trainer-employer Nim Carline had forced a rhubarb, it would probably have been a stick that could hand it out), in her training, racing, and in her sudden death.

Hilton, an art-historian, also loves the iconic moments of the sport: Rene Vietto’s tears after a Tour-losing piece of self-sacrifice, the ever-reckless Simpson running out of luck, strength and life on Mont Ventoux. He also has a fine ear for the Homeric utterances of the great riders: Eddie Merckx’s comment on Liege-Bastogne-Liege (which he won five times) was the superb: “If the Tour of Flanders had been that hard, I would have won that race more often too” – Achilles could not have put it better.

The style of narration makes the book always interesting and unpredictable, for Hilton grandly follows his own preoccupations: as he thinks that the particular rituals of club life, down to the protocols of cross-toasting at club dinners, have to be recorded, they are, in loving detail. The story of the inception of the Isle of Man week, and its nature (“land of kippers and fairy lights!”), gets his full attention. He knows his roads, and loves to evoke France and the other heart-lands of cycling, caught in some vivid phrases (“the Flemish national character is opposed to hairpin bends … Spring in Flanders is a specialised form of Winter”). He traces the pave tracks around Roubaix with the reverential intensity of one of Bruce Chatwin’s Aborigines following a songline; the route has for him a “historical resonance” which almost occludes the present. The race, or ordeal, is an annual ritual, with an occult compulsion of its own, its running a dreamtime possessing the whole Flemish nation.

There is no attempt to be inclusive, either as a historian of racing, or as a social historian of cycling in Britain. There are some parts of the book which perhaps show Hilton dutifully doing his bit, where many others have written before him (especially on the Tour itself). But this book is more concerned to record, before they are forgotten such things as: the singing club run (which died out in the 50’s, he thinks); cycling poetry; how former Desert Rats founded the ever-dwindling Buckshee Wheelers; long-lost cycle-tracks (including, to my amazement, the one where I once saw my late father do rather well in a slow bike race, at the Staveley Works sports ground); and tales of the perhaps wholly legendary Rosslyn Ladies Cycling Club.

Hilton’s style, too, is the man himself. He loves to tell you a fact, and tries elsewhere to make his own opinions sound as much like facts as possible. At times, you have to wonder who could have reported the things that Hilton so authoritatively asserts as seen and said. Did a novelistic impulse fill out the advice of Louison Bobet’s brother to a rider desperate for Tour success, and humiliated by a series of defeats (p.221)? You wonder whether his detailed account of the day to day routine of Frank Patterson hasn’t been lifted by fancy too, maybe as a deliberate tribute to the artist, imitating him in words as persuasively evocative as the illustrator’s own spindly pen-strokes, shading off into expanses of white paper suggestive of the unknown distance. Hilton points out how the intensely unsociable Patterson habitually depicted cyclists (usually solitary, and almost invariably men) finding their way across what can be interpreted as the half-emptied rural England after World War I. Are they revenants swathed in cycle capes, dead Tommies still riding in their puttees, or haunted survivors? Hilton reveals that Patterson always worked up such images from photo postcards, capturing the essence of cycling – and maybe something else – but never himself participating.

Our author too may be meticulously recording the past, but isn’t so obsessive as to exclude the future. In fact he quite explicitly seeks his younger self: before a spring classic, he believes he sees himself, rejuvenated in the shape of a reporter interviewing the riders, until the discovery that the group of young men are talking about what he terms, in distaste, ‘disco-music’ dispels the pleasant illusion. The book ends when Ulysses finally meets Telemachus: a young man chats to him while waiting to pass up a bottle at a Junior Road Race Championship. “Rarely have I seen a young person look so eager and happy”, affirms the author. Confident of his future prospects on the bike, secured for happiness by an attachment that has been Hilton’s own, the unnamed lad finally confirms his membership of the two-wheeled elect by announcing that he has just secured a job as a postman.

On clubs themselves, Hilton is both loving – during a longish trawl through his list of club names, he pauses briefly over a club ancestral to the Reading CC, the ‘Bon Amis’ (briefly noting, without any teacherly admonition, the bad French grammar in that non-agreement between adjective and noun). Clubs, he says, in a survey of the likely personnel, have “too many schoolmasters (who often are their club’s secretaries)” – so that’s me in my place then. He avers that the maximum size for a club is 100, the optimal size about 80. His bald assertion that beyond 100, a club is bound to split, has half-worried me, such is the authority with which he makes his pronouncements

And he is right to want to record a culture that is changing, or even disappearing. Time trial classics that have gone, particularly the Bath Road100, ‘haystack nights’, 21,000 cyclists converging on Meriden, at the geographical heart of England (this was in 1921) for the one of the annual cyclists’ memorial services: things like these come under his compendious remit. Alongside such things, he always tells of the doing of great deeds, and always of Coppi. Fausto training in the Alps, for instance: eight team-mates would set off up the chosen col, at one minute intervals. Then Coppi would follow, pass them one by one, and ride on up to the top alone. For ours is a heroic sport. We are a clan that orally retells the achievements of the great riders almost as fervently as the bards told of Beowulf’s exploits. We still have, in club-room, village hall, or café (rather than the meadhall), the Anglo-Saxon mode of ‘the boast’: telling what you will do, and then making the effort to live up to it, once in battle. So, hail Tim Hilton: cycling’s elder, re-teller, witness, bard: or to give him the accolade, from French usage, that he would most wish, and deserves, gentleman cyclist.