I have become interested in early advertising materials. I have posted about some early single sheet ‘bills’, including some by doctors. As the 17th century advanced, doctors began to produce quite lengthy pamphlets which described their diagnostic skills and curative regimes. I have a professional interest in materials related to witchcraft. Yesterday, I came across a pamphlet which, remarkably, combines the two, and which stands as a bridge between two worlds, the early modern, and a world that is something recognisably like our own.

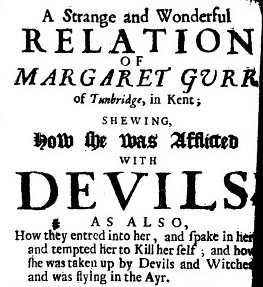

It is by Dr John Skinner, who describes himself as a ‘Student in Physick and Astrology’. ‘Astrology’ is perhaps as far as he dare go in advertising his real skills, as a private exorcist (as well as a being a doctor). The date is 1681. By this date, belief in witchcraft was well on the wane, at least in educated circles, but Margaret Gurr (his main subject, of Tunbridge in Kent, a servant) was accosted by two devils, who tempted her to commit suicide. This was quite a normal way for people to rationalise their worst impulses; to externalise them as diabolic in nature. One devil wants her to hang herself from the ‘Clock-Lines’ in the room (I’m not sure what they can be), while the other prompts her to thrust knitting needles into her ears. This was on the 19th July; on the 4th August, one of the devils enters into her, followed by a witch who also possesses her, saying: ‘Do as I say, and do as I would have you, and (be) as I am, for I am a Witch, a Witch, I am a Witch, do as I say and be as I am, and you shall be well.’

So far, so vivid, and plausible in its kind. The material consists, purportedly, of words ‘taken from her mouth Verbatim as she spake them’. But Skinner’s guiding hand appears when the witch says ‘I would not have you go to Doctor Skinner that Devil for help’. Poor Margaret gets worse, being tempted to curse at prayer time, and acquiring a rictus. On August 6th, as she is fetching pails of water. The devils abduct her aerially: ‘I was catcht up with the Devils, and was carried about with them, flying in the air’. This is a surprisingly normal symptom: it was the 17th century version of alien abduction. Skinner has clearly been consulted, and has told her to pray whenever she is tempted (it seems, tempted to yield to the Devil in another episode of flying). The Witch speaks from inside her again: ‘Go you not to that Devil Doctor Skinner for help, for if you do, I am utterly undone.’ (The forces of evil do not seem very subtle!)

Unassisted prayers do no good, the voices inside get more incessant, and she is ‘carried up and down with the Devils’ in perhaps further episodes of what she experiences as flight. Then, suddenly: ‘But with the Blessing and help of God, Doctor Skinner cast out the Devils and Witch out of my body, and also Cured me of the scurvy and Gout, and all within the compass of twelve days’. Furthermore, with her cure has come a spiritual benefit: ‘I knew not any Letters in the Bible or Testament, but since my enduring this heavy punishment … I can now learn my Book, and am wonderfully delighted in Reading and spending all my spare time in Prayers.’

Between two worlds: in this grubby little pamphlet, the world of Institoris and Sprenger is breathing its last: devils, witches, aerial abduction. A self-appointed expert leads on the simple and afflicted woman, coaxing her to say the words he wants her to say: but not to get her to confess to her pact with the devil, so as to burn her as a witch, but (and here the modern world appears) rather to secure a testimonial from her, so that he can start to make some real money. Two devils and a witch exorcised, scurvy and gout cured, and (no doubt with heaven’s help), a miraculous attainment of adult literacy: what more could anyone want from a doctor?

In the rest of the pamphlet, Skinner deals with another case of possession, and two more purely medical emergencies. The other possession case is almost as interesting as Margaret Gurr’s: a pious 17 year old servant boy, to whom the devil appears and astonishes him with the dire words: ‘You must go into

Skinner has been adroit enough to see that if he dresses up his advertising material as a case of witchcraft and possession, it will be read more avidly. In this horror movie of his own directing, he is himself the product placement. Four witnesses sign to Margaret Gurr’s testimony, exactly as would be done in those adverts based on ‘unsolicited testimonials’. But if the suicidal Margaret was restored to physical and mental help, Skinner’s odd mix of ‘Physick’ and exorcism wasn’t solely exploitative.

In Edward Ravenscroft’s play, Dame Dobson; or the Cunning Woman (1684), a servant girl, after much cajoling, finally manages to get out that she would like the cunning woman to create a magic potion that will enlarge her ‘bubbies’.

I always enjoy seeing these odd reflections of the present in these old and tarnished mirrors.

1 comment:

I've been using the Old Bailey Proceedings Online as a resource for a while, and very recently discovered that apart from the trial reports, this is a terrific source for late 17th/early 18th century adverts as well. And a lot of them seem to be for 'medical' services of various kinds.

http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/

http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/proceedings/advertising.html

By the way, I've fallen in love with this blog. You're doing wonderful things here.

Sharon

Post a Comment