A busy week for me, with a return to teaching, and four lectures to give: and hence, no mid-week surfacing by the whale. I gave one session to our new MA students in which, having conscientiously shown them the way to 'Instute' and 'The Voice of the Shuttle' literary portals, I steered them towards a webpage I put up giving links to academic blogs - and my thanks to Sharon Howard at 'Early Modern Notes' for a major hand in the selection. They all seemed delighted by what they found.

The best thing this last week for early modern era scholars has been, I think, Michael Monpurgo's series on the History of Childhood reaching the Puritan child:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/history/childhood/

The gruesome inculcations of 'learn to die' delivered by some of the earliest books aimed at children were very effectively delivered by having the adult voice (reading out the Puritan writer) fade into the voice of the child recipient of such spirit-quenching ghastliness.

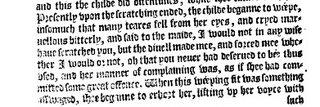

It came back to me while giving the introductory lecture on my 'Witchcraft and Drama' course, where I talk about the case of the 'Witches of Warboys' in 1593. That pamphlet doesn't show children as victims of a miserable ideology: in its highly detailed but credulous account, the Throckmorton children, led by the three eldest girls, utterly subvert their devout household, and contrive the deaths of a neighbouring family, by turning back hatred of life, transformed into murderous hostility. With astounding hypocrisy (I extract, above, one of the children's "Oh that you never had deserved to be thus used" -said to one of the victims, after 'scratching' her face), an astonishing consistency of purpose, and sustained by the household's implicit faith the the power of the devil, the girls both got to do pretty much as they pleased (play cards and bowls), and kill three people.

No-one intervenes effectively, but simply goggle in pious and complacent horror. The local clergyman takes the 'no smoke without fire' line about the accused, like King James did: if God allows you to be accused (by innocent children) it must be true. He fails to test the veracity of the children by, say, professing that he will read Psalm 51 in Greek to the possessing devil sent by the witches, and substituting a passage of Sophocles. They get their way unchecked, and contrive judicial murder.

One can only imagine that the two adults in the family they destroy suffer as surrogates for their latent hostility to their own pious parents, and that they punish their own filial wickedness in having the daughter Agnes hanged: the wretched Agnes whom they always cast, scandalised, as a daughter who beats her own Mother.

One older daughter develops advanced blanking techniques, in which, notionally steered by the devil the witches have put into her, she will only acknowledge the presence of the adult who has been dragooned into playing cards with her (so as to stave off her fits). The third daughter, in the other extract I give above, develops this further, professing to be simply incapable of seeing adults, while she can see items of clothing moving in the air. Making adults disappear by imaginative means is one thing: but of course, they went to the extreme of making adults disappear terminally.

Utterly remarkable, and not without precedent, but showing what children could do with the idea of the devil. It does seem curious that Puritan thinking (yes, they are a little early historically, but within the Anglican church, that's the way the family seem inclined) didn't alert the adults to the possibility of wickedness among children, but throughout, these gentry children are assumed to be innocents, driven by the devil to their cruelties, hapless instruments of the spirits who are determined to expose the witches.

But the child as perpetrator was probably not a line that Mr Monpurgo and his researcher wanted to take.

No comments:

Post a Comment