One of my students is writing a third year dissertation on sleep in Shakespeare: not dreams, just images of plain sleep. I've a feeling that a critical piece by David Roberts on this very subject may be hard to shake off.

One of my students is writing a third year dissertation on sleep in Shakespeare: not dreams, just images of plain sleep. I've a feeling that a critical piece by David Roberts on this very subject may be hard to shake off.But I've duly gone through a couple of early modern home doctors, talking about sleep (Humphrey Brooke, 1650, and Tobias Venner, 1637). Pretty much as one would expect - a lot of spurious advice, and that very English mania about the digestion (start off lying on your left, then turn onto your right, as that sequence aids 'decoction'; never on your back or you invite 'the Nightmare', and only under advice lie on your stomach). I suppose that we can draw some fine points about the type of conclusions audience members might have drawn had they seen Innogen or Bully Bottom lying flat on their backs.

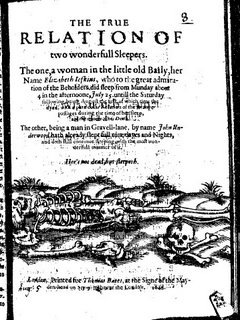

But what turns up as well are the pamphlets and broadsides about 'wonderful sleepers': those who slipped into (I suppose) an encephalitic coma and who could not be roused by nose-tweakings, pinches, and dashings with water. The pamphlet illustrated has a healthy middle-aged woman going to bed in the daytime, falling and staying asleep, and finally dying without ever waking up again. The last paragraph gives some sense of the desperate haste of the compiling author to finish his copy, and not be drawn into too prolonged an investigation - for even as he writes, news of a second sleeper has come in (just when he'd got the job nearly done too!):

Whilst we were endeavouring to satisfie our thoughts on this melancholy contemplation, Newes is brought, that a man lies fast on sleep in the same manner in Gravell-Lane, I was desired to go and see him, to the end, that having taken a perfect observation of him, my Pen, my more readiness might follow the instructions of my eye: His name is as I am informed John Underwood; His age is about forty, or something upwards; And he sleeps so soundly, that they who have seen him tell me that you may heare him into the next roome. We heare that he hathe already slept out the full space of nine daies and nights: It seemes he is of a clear complexion, for his breast being uncovered, that the beholders might be the better satisfied, it is reported that the bitings of the Fleas upon his Necke and Brest, do looke like to many Strawberries strowed upon Creame. It is true in the Metaphysicks, that the outward sences being overcome by sleep, the Soule (incapable of sloth) doth actuate at that time more pure and lively. The people in the Suburbs have gained some little understanding of it, and therefore they come every day in crouds unto him, expecting when he awakeneth, to heare some wonderful intelligence.

I like (I recognise!) the way the author couldn't in fact be bothered to go along himself, but offers instead a secondhand report of the small crowd gathering at the sleeper's bedside in the expectation that he will have some remarkable vision to recount when or if he wakes. They'd all been reading too many broadside ballads in the vein of Saint Bernard's Vision. In the absence of L-dopa, not very much anyone could do - though they could at least have tried to get rid of the fleas.

1 comment:

There was a seminar on sleep in early modern England at the ISA congress in Brisbane, led by Lyn Tribble and Garrett Sullivan. Might be worth chasing them up?

Post a Comment