I’ve been doing a lot of teaching, and among my texts, the very familiar Witch of Edmonton. Doing this prompted me to do what I haven’t previously bothered to do, that is, read all the writings of Henry Goodcole (usually mentioned only as the writer of the pamphlet used by Dekker, Ford and Rowley for that play).

The brief Oxford DNB entry on Goodcole mentions a series of salary increases and, later, a substantial loan he elicited from the court of aldermen in London – a body that at one point doubled his salary without any prompting. As ‘lecturer’ at Ludgate prison, then ‘visitor’ at Newgate prison, Goodcole clearly pleased his employers, and, looking at his pamphlets, one can see why.

Goodcole was assiduous in his praise of the system he served, and those who controlled it. His role began after the felon had been condemned: he dealt with the frightened, resentful, anguished or stupefied products of the brusque Elizabethan courts, which handed out sentences whose horrors in actual execution would in all likelihood have been well known to the condemned. People went en masse to see executions, and the recently executed: in one of his pamphlets Goodcole mentions those who owned the land adjacent to a gibbet petitioning successfully to get the executed man moved further away, so flattened were crops in its vicinity.

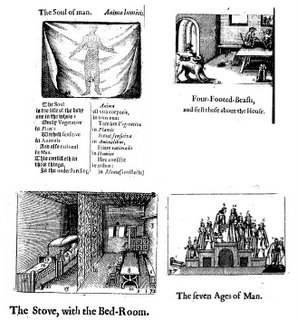

He represents himself (and probably was) as being highly conscientious in his duties. His recurrent image is of himself as a doctor to something more important than the body, the soul, and ‘Physitians of the Soule ought to immitate those learned Physitians of the body, [with] frequent visitations of those sicke patients, whose diseases are desperate and inveterate’ (The adultresses funerall day). ‘Miserable end, when men end in their sinne’ (Prodigall’s Tears, p.142), was his guiding thought, and he laboured to produce proper contrition in the condemned. Of course, he writes up his successes. The multiple murderer Thomas Shearwood, whose use of Elizabeth Evans as a decoy to lure his victims to their deaths impresses Goodcole as a new and unparalleled wickedness, died (in Goodcole’s view) in a valuable manner: “his death he joyfully embraced, and mortall life cheerfully did surrender up, and sent his soule out of his Body flying, calling on the name of the Lord Jesus to receive him. And all the people speaking to God for him, likewise with their lowd voices, and strong acclamations, Lord Jesu take mercy on him, sweet Jesu forgive his sinnes, and save his Soule”.

Goodcole lived a life you would think of as potentially traumatic, or brutalising, being in attendance at execution after execution. His writings manifest a typical ‘puritan’ concern with blasphemy – cursings bring the devil to Elizabeth Sawyer. A truculent end on the gallows is something he considers “most desperate, deuillish and damnable, and sauours no whit of the least sparke of Gods grace”. He wants to hear the right words, for the execution to have more than an aspect of a religious rite, with a congregation responding properly. Francis Robinson, a gentleman hanged, drawn, and quartered for forging the Great Seal of England and using it for fraudulent gain, was an ideal subject. Goodcole transcribes all Robinson’s prayers, and, at the end: “Like a Lambe going to the slaughter so went he unto his death, prepared before to suffer the same, willingly, patiently, and joyfully: and our confidence is such of him, that he is receiued into the Fold of that most blessed heavenly Flocke”.

That final note is one Goodcole recurrently makes: Londons Cry Ascended to God ends with solemn thoughts: ‘Judges, Men made of earth, turnes these miserable wretches unto the Grave, Dust, and Earth’, but then reflects that ‘they shall rise out of the dust of their Graves; for their Corruption, then to put on Incorruption’. He is apparently perfectly convinced that punishment here, and reconcilement to the true faith, will save the soul of the condemned.

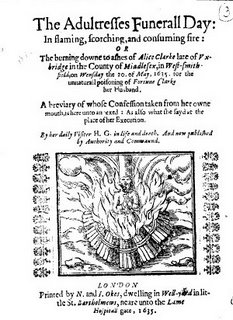

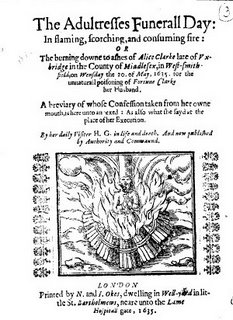

His most dramatic intervention came in the case of Alice Clark, who faced being burned at the stake for her adultery and murder: “Uppon Wensday morning, on which shee was executed, there assembled unto Newgate multitudes of people to see her, and some conferred with her, but little good they did on her, for shee was of a stout angry disposition.” Goodcole decides that, like Barnadine in Measure for Measure, she was, in her state of mind, “no fitting guest for the Table of the Lord Iesus”. He then plays his last card: “thereupon, I made as though I would have excluded her thence, in denying the benefit of the holy Communion, of the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ, inferring the benefit of the unspeakeable blesse, by the worthy receiving of it by Repentance and Faith, and the most woefull malediction to all impenitent and unworthy receivers. Whereupon, it pleased God, so to mollifie her heart, that teares from her eyes, and truth from her tongue proceeded, as may appeare by this her ensuing Confession at the very Stake”.

He is convinced that his clients will go be saved if they die contrite, and that helps Goodcole with his dreadful duties. He also believes in a God whose anger is the model for the judicial system he so piously endorses. Londons Cry Ascended to God has the running title ‘Londons Cry for Revenge’. God’s anger is assumed, and is unquestionable, even if not always very discriminate.

Goodcole’s pamphlet A true relation of two most strange and fearefull accidents (1618) is largely about the death of a man taking the Lord’s name in vain with a false oath: “if I sweare amisse, (quoth he) or if I speake wrongfully, let God I beseech him make me a fearfull example to all perjur’d wretches, and that this house wherein I stand, may sodainely fall upon my head, and that the fall thereof may bee seene to bee the just judgement of God upon me”. That the court house collapsed at that very moment manifests God’s wrath. Goodcole is undaunted in detailing the multiple fatalities, including “certaine Esguires and Gentlemen of good calling, by the fall of the said walls and timber, [who] were sodainly strooke dead”.

God’s anger being so splattery in its operation, Goodcole was not going to baulk at the rough judgments handed down at court, which zealously imitates the divine displeasure (perhaps with a sense that if they act quickly, they prevent some larger chastisement). Maybe just once he almost wavers: he interlaces his zealous account of Alice Clark going to the stake with a tale of an unnamed woman, who he knows was abused hideously by her old and ‘peevish’ husband, and who resolved to poison her husband, then commit suicide. She administered the poison, but repented what she had done. The consequences were extraordinary:

But better motions now comming into her thoughts, and she truely repentant of what she had done, finding the confection begunne to work with him, fell downe before him upon her knees: First acknowledging the fact, then humbly desiring from him forgivenesse, with all, beseeching him to take some present Antidote to preserve his life, which was yet recoverable: on whom he sternly looking, as he lay in that Agony gasping betwixt life and death, returned her answere in this manner; nay thou Strumpet and murderesse, I will receive no helpe at all but I am resolvd to dye and leave the world, be it for no other cause, but to have thee burnt at a stake for my death: which having said, and obstinate in that Hethenish resolution, he soone after expired.

Goodcole clearly regards her case as having been a hard one, but they had duly carried out the judicial murder her horrible husband anticipated.